Saturday, December 13, 2014

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Thoughts on Infallibility (Article IIIa): On That Which the Church Does Not Teach

The Series Thus Far:

Introduction

Now that I have dealt with Peter, his primacy and that he made decisions for the Church which were either protected from error or else throws the entire belief of Christianity into doubt, it is time to move on to what some people might have wanted me to cover from the beginning — the belief of Papal Infallibility itself.

However (you knew there had to be a catch, didn't you?) before we can do this, we effectively need to define what it is not.

Two Forms of Rejection

There tends to be two forms to the rejection of the authority of the Church as binding.

- Those who reject the Catholic claim of infallibility and that the Church can be free from error when she teaches.

- Those who deny that a part of Catholic teaching, which they dislike, is binding.

Non Catholics tend to fall into the first group. Because they believe the Catholic Church teaches wrongly, it makes sense they would not believe that the Catholic Church could be protected from error. Some Catholics fall into the first group, but unlike the non-Catholic, they are being hypocritical for remaining within the Church when they reject what it teaches on teaching without error.

The second position tends to be held by Cafeteria Catholics (Catholics who arbitrarily choose which teachings they will follow and which they will not). Such individuals deny they are at odds with the Church, their argument going as follows:

- I am a faithful Catholic

- I am at odds with the Church on Teaching X.

- Therefore Teaching X is not binding.

Such an argument is in fact based on the belief that "whatever I do is good" and those who indicate otherwise are in the wrong. Ironically such a view denies that the Church itself can be infallible, but insists on the infallibility of the self in a way far beyond what the Church teaches on the subject.

What Catholics DO NOT Believe on Infallibility

The first step for this section of the series is to eliminate what is outside of the Catholic teaching on Infallibility. I start with this because pretty much all the attacks which seek to deny this teaching are based on assumptions which Catholics do not believe. Attacks which say "What about X?" which cover material which Catholics do not believe is covered by the doctrine on infallibility would be examples of the Straw man fallacy.

So let us look at some things which Infallibility is NOT:

1) Infallibility is not impeccability. Belief that the Pope is infallible does not mean a belief that the Pope cannot sin. The Pope is a man, just as much in need of Christ's salvation as the rest of us. Therefore, people who attack infallibility on the personal conduct of some Pope do not refute infallibility.

2) Infallibility does not cover the Pope's views on a subject as a private individual. Nor is what the Pope says prior to being Pope covered by infallibility. Infallibility comes attached to the office of the Pope, and is not a personal gift. Nor does it involve subjects other than faith and morals. If the Pope says he thinks investing in Microsoft is a good idea, and Microsoft stock tanks, this does not mean the Pope is not infallible.

3) Infallibility is not prophecy. Nor is it new revelation. The Pope cannot define new beliefs (even though some Anti-Catholics accuse us of exactly this). The Pope is not like what Mormons believe of their leader. His words are not revelation from God. Now I recognize that some non-Catholic readers will say "What about X? That contradicts the Bible!" This will be a topic further on in this series. For now, the short answer is, we do not contradict the Bible, and the issue is over who has the authority to interpret what the Bible means.

4) The Pope's infallibility does not deal with the administration or governance of the Church. People who point to actions by the Papal States prior to 1870, to the handling of the Sexual Abuse scandals of today or the recent news of the Vatican Banking controversy must realize that we do not believe that such actions are covered by infallibility.

5) Infallibility is not disproved by the changing of Church disciplines. Whether the Mass is in English or Latin, whether we receive the Eucharist on the hand or the tongue, whether the laity receives both the host and the chalice or just the host… these changes do not mean the Church contradicts herself. Rather these are things the Church binds and looses depending on the needs of the faithful at the time. If for example, there is a false view that one must receive both the host and the chalice or one does not properly receive the Eucharist (as Jan Hus wrongly believed), the Church can withhold the Chalice from the laity. If the Church decides that it would be more beneficial for the Mass to be said in the vernacular or uniformly in Latin, it can make a binding decree. However, in such disciplines, the Church was not wrong then and is now right. Nor was it right in the past and wrong now. Both were decisions which fit the needs of the time.

6) Finally, Infallible teachings are not what people misunderstand them to be. If a person misunderstands a teaching of the Church (such "Catholics worship Mary!") and point to an Infallible statement as if it promotes this false understanding, the fault is with the individual who misunderstands, not with the Church which is misunderstood.

It is important to make these distinctions because essentially every attack against infallibility falls into these categories. Since Catholics do not believe infallibility is involved in these situations, any attack against the Catholic belief in infallibility which invokes these areas are false and do not refute infallibility.

There are of course more things which infallibility is not. However these will be brought up at the proper time (such as the "If it isn't declared infallible, it's merely an opinion and I can ignore it" canard so beloved by modernists and traditionalists).

To Be Continued

In the next article, I intend to move on to what the Church DOES teach about infallibility.

Thoughts on Infallibility (Article IIIa): On That Which the Church Does Not Teach

The Series Thus Far:

Introduction

Now that I have dealt with Peter, his primacy and that he made decisions for the Church which were either protected from error or else throws the entire belief of Christianity into doubt, it is time to move on to what some people might have wanted me to cover from the beginning — the belief of Papal Infallibility itself.

However (you knew there had to be a catch, didn't you?) before we can do this, we effectively need to define what it is not.

Two Forms of Rejection

There tends to be two forms to the rejection of the authority of the Church as binding.

- Those who reject the Catholic claim of infallibility and that the Church can be free from error when she teaches.

- Those who deny that a part of Catholic teaching, which they dislike, is binding.

Non Catholics tend to fall into the first group. Because they believe the Catholic Church teaches wrongly, it makes sense they would not believe that the Catholic Church could be protected from error. Some Catholics fall into the first group, but unlike the non-Catholic, they are being hypocritical for remaining within the Church when they reject what it teaches on teaching without error.

The second position tends to be held by Cafeteria Catholics (Catholics who arbitrarily choose which teachings they will follow and which they will not). Such individuals deny they are at odds with the Church, their argument going as follows:

- I am a faithful Catholic

- I am at odds with the Church on Teaching X.

- Therefore Teaching X is not binding.

Such an argument is in fact based on the belief that "whatever I do is good" and those who indicate otherwise are in the wrong. Ironically such a view denies that the Church itself can be infallible, but insists on the infallibility of the self in a way far beyond what the Church teaches on the subject.

What Catholics DO NOT Believe on Infallibility

The first step for this section of the series is to eliminate what is outside of the Catholic teaching on Infallibility. I start with this because pretty much all the attacks which seek to deny this teaching are based on assumptions which Catholics do not believe. Attacks which say "What about X?" which cover material which Catholics do not believe is covered by the doctrine on infallibility would be examples of the Straw man fallacy.

So let us look at some things which Infallibility is NOT:

1) Infallibility is not impeccability. Belief that the Pope is infallible does not mean a belief that the Pope cannot sin. The Pope is a man, just as much in need of Christ's salvation as the rest of us. Therefore, people who attack infallibility on the personal conduct of some Pope do not refute infallibility.

2) Infallibility does not cover the Pope's views on a subject as a private individual. Nor is what the Pope says prior to being Pope covered by infallibility. Infallibility comes attached to the office of the Pope, and is not a personal gift. Nor does it involve subjects other than faith and morals. If the Pope says he thinks investing in Microsoft is a good idea, and Microsoft stock tanks, this does not mean the Pope is not infallible.

3) Infallibility is not prophecy. Nor is it new revelation. The Pope cannot define new beliefs (even though some Anti-Catholics accuse us of exactly this). The Pope is not like what Mormons believe of their leader. His words are not revelation from God. Now I recognize that some non-Catholic readers will say "What about X? That contradicts the Bible!" This will be a topic further on in this series. For now, the short answer is, we do not contradict the Bible, and the issue is over who has the authority to interpret what the Bible means.

4) The Pope's infallibility does not deal with the administration or governance of the Church. People who point to actions by the Papal States prior to 1870, to the handling of the Sexual Abuse scandals of today or the recent news of the Vatican Banking controversy must realize that we do not believe that such actions are covered by infallibility.

5) Infallibility is not disproved by the changing of Church disciplines. Whether the Mass is in English or Latin, whether we receive the Eucharist on the hand or the tongue, whether the laity receives both the host and the chalice or just the host… these changes do not mean the Church contradicts herself. Rather these are things the Church binds and looses depending on the needs of the faithful at the time. If for example, there is a false view that one must receive both the host and the chalice or one does not properly receive the Eucharist (as Jan Hus wrongly believed), the Church can withhold the Chalice from the laity. If the Church decides that it would be more beneficial for the Mass to be said in the vernacular or uniformly in Latin, it can make a binding decree. However, in such disciplines, the Church was not wrong then and is now right. Nor was it right in the past and wrong now. Both were decisions which fit the needs of the time.

6) Finally, Infallible teachings are not what people misunderstand them to be. If a person misunderstands a teaching of the Church (such "Catholics worship Mary!") and point to an Infallible statement as if it promotes this false understanding, the fault is with the individual who misunderstands, not with the Church which is misunderstood.

It is important to make these distinctions because essentially every attack against infallibility falls into these categories. Since Catholics do not believe infallibility is involved in these situations, any attack against the Catholic belief in infallibility which invokes these areas are false and do not refute infallibility.

There are of course more things which infallibility is not. However these will be brought up at the proper time (such as the "If it isn't declared infallible, it's merely an opinion and I can ignore it" canard so beloved by modernists and traditionalists).

To Be Continued

In the next article, I intend to move on to what the Church DOES teach about infallibility.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Thoughts on Infallibility (Interlude): Clarifying Certain Terms

The Articles so far:

Introduction

While I was hoping to go on to the Book of Acts and the Epistles, due to certain accusations against the Church which demonstrated a lack of understanding of what Catholics actually believe, I thought I should take the time to write this to clarify what certain concepts mean.

Infallibility and Impeccability

Having had to deal with and delete certain comments from an individual who has accused me of denying historical and Scriptural claims (I haven’t. Merely objected to the propagandistic distortion of them), I thought I should begin this article with a rejection of a certain attack against the Church. While I’d prefer to deal with it in Article IV (looking at what the Church claims about herself) it seems I need to deal with it now, and that is in relation to the claim of people who were in authority in the Catholic Church and did wrong.

The difference is between Infallibility and Impeccability. Infallibility means to be unable to err. Impeccability means to be unable to sin. Catholics do not believe the Pope is impeccable. The Pope, being a human being, is a sinner just like the rest of us. Therefore to point to certain sinful acts which the Popes may have carried out have no bearing on what they teach.

Infallibility needs to be broken down further to recognize that we do not believe everything the Pope says and does is unable to err. Infallibility deals specifically with the formal declarations on matters pertaining to salvation. We don’t believe that the Pope is some sort of prophet or that his writings are on par with Scripture. We simply believe that when it comes to formally teaching on matters of salvation in a binding fashion, God protects the Pope from teaching error.

In other words, we do not believe that the Pope has this ability because he is a “better” person than us. We believe that God protects Him from error when He teaches for the good of the Church.

Doctrine and Discipline

Also we need to distinguish between doctrine and discipline. Doctrine is the teaching of the Church, which one must believe if one is to be considered a believer at all. Disciplines are calls to obedience on issues which we are bound to obey but can be changed for the good of the faithful. Belief in the Trinity and the belief Jesus is God are doctrines. They have not been contradicted (though some who misunderstand what was being said think there is contradiction).

Celibacy in the Western Church is a discipline. Jesus said that those who could keep this life should do so. The Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church recognize that a married man can validly become a priest. The reverse is not true. Neither the Catholics nor the Orthodox believe that a Priest may marry without being dispensed from their vows and are usually required to stop using their priestly functions. However, at this time, the Latin rite chooses only to call to the priesthood those who can keep to the life of celibacy. The Church can make an exception, and has done so. Fr. Ray Ryland and Fr. Dwight Longenecker are examples of men who converted to the Catholic Church as married men and were permitted to be ordained.

Other examples of Disciplines are things like receiving the Eucharist on the tongue or in the hand, or receiving the Body alone or the Body and the Blood.

Depending on the needs of the faithful, the Church can bind or loosen the discipline. They cannot however loosen a doctrine. You’ll never see a Pope permit fornication.

The “Bodycount” Argument

Some people like to point to the bloody centuries of Christendom and argue that the Church ordered the execution of people they didn’t like. Therefore the Church can’t be infallible.

This is a non sequitur argument and is also a Straw man argument. The Straw man is to say that the Church ordered executions and did so arbitrarily. This overlooks the fact that during the time that the Papal States were an independent government, there were people living there who were under the civil laws. A person who was a murderer could be executed for example under the civil laws of the Papal States, just as they could in other places.

Heresy was a civil crime, on par with treason. The Inquisition was intended to investigate charges of heresy. The most common verdict was “Not Guilty” actually. When a person was guilty of heresy and refused to either leave or cease teaching heresy, they were guilty of a civil crime which the state punished.

This gets muddled in nations where the head of the state interfered with the Church. The Spanish Inquisition, for example, was a matter of excessive government control, and Torquemada was censured by Rome for his actions and warned to be merciful. We see this in Elizabethan England and in the divided Holy Roman Empire as well. When the ruler made himself the head of the Church, the acts against that ruler as head of the Church was at times seen as acts of treason. This is why the Catholic Church has always resisted the attempts at state control (called Caesaro-Papism).

So here is the reason the “Bodycount” argument doesn’t work. When the Pope was head of a state, his infallibility was not extended to his temporal rule of a nation. We wouldn’t consider Pope St. Pius V to be any more infallible in governing the Papal States than we would consider President Obama to be infallible in governing America today.

However, when a Pope decreed something that was binding on those who were in communion with the Catholic Church, it was believed that this decision was binding and was to be obeyed.

Context is Key

What one must remember when looking at Church history is that the times were different then. Capital Punishment has varied in some areas. Until the latter half of the 20th century, Rape was a capital crime in the American South for example. Different forms of punishment were used in the past which seem barbaric today. The Guillotine is barbaric today, but was used in France until it was abolished in 1981 (the last execution using it was in 1977). Burning at the Stake and the like are indeed horrible things, and it is right to feel horror at its use.

However we must remember it was not invented by the Church. It was a pagan invention, which was kept around as the barbarians (mostly the Germanic nations) were Christianized, and only gradually rejected (it lasted until the 18th century in Europe, and was not outlawed in England until 1790). It was used as Capital Punishment in both Catholic and Protestant nations.

Conclusion: So what’s the Point of It All?

So why do I bring this up? Mainly to stress that while Europe has indeed had a bloody past, this bloody past was not something which the Church made an infallible teaching about, and thus to make use of such claims is to misapply the belief of infallibility. Likewise when the Church makes a change in discipline, the change does not mean “from wrong to right,” but rather takes a discipline and looks at it in each age to see if the keeping of it benefits the faithful or whether it becomes viewed as a mere rule which brings no spiritual benefit.

For the Next Time

Assuming no more clarifications need to be made, the next article will be IId: On Peter in Acts and the Epistles.

Monday, July 12, 2010

Thoughts on Infallibility (Part IIa): Preliminaries on Peter

Preliminaries to Looking at Peter

Before moving on to the examination of Scripture, I would like to discuss some elements of historical fallacies. To study an issue, one needs to remember that a question must be framed properly. If it is framed wrong, then a person may find evidence to appeal to their claim, but that doesn’t mean the framed question is accurate to begin with.

For example, asking the question “Was Peter the first Pope?” is the wrong way of framing the question. If one believes it, one looks for evidence to show the answer in the affirmative. If one does not believe it, one looks for evidence to disprove it. Each side grows frustrated with the other side and assumes they are acting from ignorance or obstinacy.

A better question would be, “What was the role of Peter in the early Church?” This is a question which can be answered by the data of scripture and of history of the earliest Christians. We can look at it and see whether Peter played a significant role, a minor role, or something in between. We can see whether the Patristic writings speak of Peter as insignificant or important for example.

Another thing to be aware of is the issue of irrelevant evidence. Take for example, the Biblical commentary of Matthew Henry (1662-1714), who wrote on Matthew 16:18-19:

(1.) Peter’s answer to this question, v. 16. To the former question concerning the opinion others had of Christ, several of the disciples answered, according as they had heard people talk; but to this Peter answers in the name of all the rest, they all consenting to it, and concurring in it. Peter’s temper led him to be forward in speaking upon all such occasions, and sometimes he spoke well, sometimes amiss; in all companies there are found some warm, bold men, to whom a precedency of speech falls of course; Peter was such a one: yet we find other of the apostles sometimes speaking as the mouth of the rest; as John (Mk. 9:38), Thomas, Philip, and Jude, Jn. 14:5, 8, 22. So that this is far from being a proof of such primacy and superiority of Peter above the rest of the apostles, as the church of Rome ascribes to him. They will needs advance him to be a judge, when the utmost they can make of him, is, that he was but foreman of the jury, to speak for the rest, and that only pro hâc vice—for this once; not the perpetual dictator or speaker of the house, only chairman upon this occasion.

Peter’s answer is short, but it is full, and true, and to the purpose; Thou art the Christ, the Son of the Living God. Here is a confession of the Christian faith, addressed to Christ, and so made an act of devotion. Here is a confession of the true God as the living God, in opposition to dumb and dead idols, and of Jesus Christ, whom he hath sent, whom to know is life eternal. This is the conclusion of the whole matter. (Matthew Henry's commentary on the whole Bible)

Now, that other apostles had a role in speaking on some issues is not denied. The question is whether or not his examples are relevant for this section of Scripture prove Peter was not the head of the Apostles. Henry’s examples do not answer the question, “What was the role of Peter?” Rather these examples seek to give a negative answer to the question “Was Peter Pope?” in the sense of the papacy at the time Henry knew it.

Third, we need to be aware of biased language. If I speak of “Idiot Protestants” and “Insightful Catholics” this could be considered a clue that my investigations in the matter were not entirely free of bias. (To put it mildly!) Now of course, I am a Catholic because I believe the Catholic teaching to be true. I know there are those outside the Catholic Church because they do not believe it to be true, and in such a dispute it is searching for the truth which matters, not the exchange of insults or ad hominems. However, we do need to be aware of “charged” language which does seek to take the reader to a conclusion based on the choice of words. Mentioning Peter’s temper and terms like “perpetual dictator” are terms calculated to create a negative view of primacy for Peter, and thus be predisposed to reject it.

In order to reduce the risk of bias (and let’s face it, Christians do have a vested interest in the truth about the primacy of Peter, and the result we believe is true is not agreed on by all Christians), we need to be aware of these issues, and seek to recognize how we are to keep them from hindering our search for the truth, and not assume that what we believe ought to be apparent to all.

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Thoughts on Infallibility (Part I): Preliminary Logic and Syllogisms

Introduction

The disputes between the Catholics and the Protestants often come down to a dispute on the claim that the Church teaches authoritatively in a binding manner which can be free of error. This article deals with logic and syllogisms which express these things.

I do not claim these syllogisms are the only ones. Rather this is my own take on the topic.

I start with logic, rather than Scripture, not because I think Logic is greater than Scripture, but because before we look at Scripture we need to be aware of certain assumptions which people hold uncritically and see if it is reasonable to hold them.

This will be multi-post, but the posts will not necessarily come one after the other

Preliminary Notes

- This article is not meant to address all issues of infallibility. Nor is it intended to prove it to the non-Christian audience. Rather it presumes the reader accepts the existence of God (for a reader who does not accept the existence of the Triune God is therefore not a Christian). It intends to look at the Christian dispute over whether or not God can grant His Church the ability to teach without error in certain circumstances.

- Obviously if one does not believe in God, it follows he or she won’t believe God can make His Church infallible either, so it's a moot point for the unbeliever to begin with.

- These are my own thoughts on the subject, and not the official teaching of the Church on infallibility. So if you find some point of disagreement, don't go announcing how you "disproved the Church teaching."

Non Christians are of course welcome to read this, but please spare me the “you didn’t prove God exists!” comments. Christians don’t need to prove God exists before discussing theological issues among themselves any more than physicists have to prove the existence of matter before starting work on a scientific project… it’s an essential premise. (No recognition of the existence of God as a precondition, no discussion of Christianity. No recognition of the existence of Matter as a premise, no discussion of Physics)

Definitions

There are some terms which need to be defined. These definitions come from the OED (no, I didn't alphabetize them. Windows Live Writer can be a pain in this way):

- Infallible: incapable of making mistakes or being wrong.

- Fallible: capable of making mistakes or being wrong.

- Inerrant: incapable of being wrong.

- Personal: of, affecting, or belonging to a particular person.

- Inspired: fill with the urge or ability to do or feel something

- Interpret: explain the meaning of (words, actions, etc.)

- Error: a mistake, the state of being wrong in conduct or judgment.

- Literal: taking words in their usual or most basic sense; not figurative

- Symbol: a thing that represents or stands for something else, especially a material object representing something abstract.

- Plain: easy to perceive or understand; clear

- Sense: a way in which an expression or situation can be interpreted; a meaning.

- Contradictory: Logic (of two propositions) so related that one and only one must be true.

- Contrary: Logic (of two propositions) so related that one or neither but not both must be true.

- Syllogism: a form of reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two given or assumed propositions (premises); a common or middle term is present in the two premises but not in the conclusion

- Essential: central to the nature of something; fundamental

- Arbiter: a person who settles a dispute.

Now these terms can have deeper meanings in the theological sense, but these at least give a basic understanding of the terms

The first set of syllogisms:

Because we Believe God protected the writers of the books of Scripture from error, we must recognize that God protected the Church from decreeing error when it proclaimed what was contained in Scripture.

This set of syllogisms (#1-4) assumes that Christians believe in the authority of Scripture (again, the denial of this makes one a heretic at the very least). Because Christians believe God is all powerful and He made scripture inerrant, these are elements of common ground we share even if we disagree on other issues. So let’s use this as a starting point.

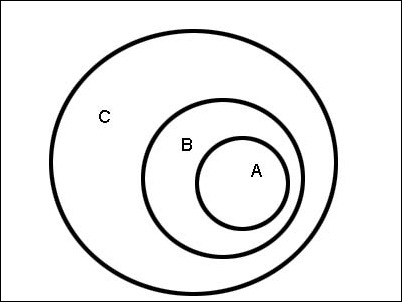

Syllogism #1

- For [something to be unable to err], it must be [all knowing and all powerful] (All [A] is [B])

- [God] is [all knowing and all powerful] (All[C] is [B])

- Therefore [God] is [unable to err] (Therefore All [C] is [A])

A Christian which denies this is seriously deficient in their faith.

If God is not all knowing, there can be things He does not know and thus can err. If God is not all powerful, there can be things He cannot access and thus He can again err (also known as inerrancy). Now we accept that God is all powerful and all knowing and is this inerrant. How does humanity fit into this? Let us move on to the second syllogism.

Syllogism #2

- [Inerrancy] requires being [all knowing and all powerful] (All [A] is [B])

- [Man] is not [all knowing and all powerful.] (No [C] is [B])

- Therefore [man] is not [inerrant]. (Therefore no [C] is [A])

This is important to remember here. No man can claim to be free of error on his own, because man is not free from error. So a person who claims to be unable to err must either get his ability from a greater [all knowing and all powerful] being or else be lying or deceived.

Syllogism #3

- Christians believe that the [Bible] was [inerrant] (All [B] is [A])

- The [Bible] is something [written by man] (Some [C] is [B])

- Therefore Christians believe something [written by man] can be [inerrant] (Therefore Some [C] is [A])

However, since we already went through the fact that man is not inerrant, it follows that for something created by a man to be inerrant, the ability to be inerrant has to come from a being which is inerrant (which Christians call God), and is not independent of God.

With this done, we need to take a brief look at the history of the canon of Scripture.

Logic and History

We need to start with the Christian recognition that the Bible neither contains books that were not inspired, nor excludes books that were inspired. So if we are to say the Bible is complete and inerrant, it means that nothing within the Bible is present wrongly and nothing is excluded wrongly from the Bible.

However, there were disputes in the past. Not over everything of course. The Gospels, the Epistles of Paul, 1 John and 1 Peter were all generally recognized by faithful Christians. However, some thought that Hebrews, James, 2+3 John, Jude and Revelation were inspired and some rejected this. The decision was made by the Church in the 4th century was considered to have settled the matter.

Now, remember that if the Bible is to be considered inerrant as a whole and in its parts, the decision had to have been protected from error. Otherwise we could not know the Bible was inerrant as a whole and in its parts.

Since the list of books approved for the Bible was composed in the late 4th century AD, and recalling that it takes a being that is [all knowing and all powerful] to make something inerrant, we can’t say that God was only involved in making something inerrant at the time of composition of Scripture.

Remember if the list of Scripture is not inerrant, we cannot know whether or not the books in the Bible belong there. If we can’t know if the books within the Bible belong there, we can’t know it is unable to err. Therefore if we believe the Bible is inerrant, we must accept that the list of books in Scripture is inerrant.

So that brings us to syllogism #4 which will continue to advance the issue.

Syllogism #4

- The Church [decreed] [the list of scripture] (A is part of B)

- 2. This [list of scripture] is [inerrant] (B is part of C)

- 3. Therefore the Church [decreed] something [inerrant] (Therefore A is part of C)

We then must recognize that the Church was free of error at least once, and that the cause of infallibility is God then we need to recognize that God can will the Church to be free of error in certain types of teachings.

Now of course, we haven’t yet reached the concept of establishing the Church is infallible as she claims, but we have demonstrated with logic that the Church can be protected from error by God when it teaches something essential for salvation (in this case declaring what makes up the Bible).

Those who wish to claim the Church was only inerrant here and not elsewhere need to establish their point just as Catholics need to establish that the Church was kept free of error more than once.

The Second set of Syllogisms: On the need for a single arbiter of Scripture

Some argue that “Scripture must be interpreted by Scripture” and appeal to the “plain sense of scripture.” The problem is that some appeals to these issues lead to contradictory readings of Scripture.

In theological terms this expression is used traditionally to refer to the “literal” or supposedly “plain” sense of Scripture, which holds that the biblical texts need not be studied and interpreted, but rather simply applied and followed. So theoretically, if you and I both read a passage, we should get a meaning which is similar

(Let me remind the reader, that when things are contradictory, only one of them can be true: “It is either white or not white”. When things are contrary, they can’t both be true but both can be wrong: “It is either black or white” is wrong if it is orange)

Since the personal interpretation of Scripture often contradicts or is contrary, we can make the following syllogisms:

Syllogism #5

- [Plain sense] of Scripture is something which is [apparent to all]

- Some [Readings] of Scripture are not [apparent to all]

- Therefore Some [readings] are not [plain sense] of Scripture

So here is the problem. When two people interpret Scripture in a way which is contrary or contradictory, they can’t both be right (and if the reading is “contrary” both could be wrong). So who is authoritative to determine who is right and wrong when it comes to the reading of Scripture?

This isn’t merely a sense of Catholic vs. Protestant or Protestant vs. Protestant. We have had in history things like Trinitarian vs. Arian, Trinitarian vs. Nestorian, Trinitarian vs. Modalist, and so on. In all of these cases, the heresies appealed to Scripture in order to claim that the Church was in error when teaching in favor of the Triune God.

So we can see that there is a problem with the personal reading of Scripture: the person who reads Scripture with an error in what he or she believes about God can, as a result, read Scripture wrongly if their interpretation is wrong.

So let’s look at Syllogism #6:

Syllogism #6

- Every [Personal Interpretation] is [Individual] (All A is B)

- All [Individuals] [can err](All B is C)

- Therefore [Personal interpretation] [can err](Therefore all A is C)

[Edited to fix a fallacy of the undistributed middle which slipped by me]

Since we believe God is truth, and truth does not contradict truth, it follows that whatever God inspires will not contradict other things He inspires. Thus as Christians we reject Islam as contradicting what was revealed about Jesus. We don’t believe that the Old Testament contradicts the New Testament however.

“The Holy Spirit inspired this interpretation” is the common explanation for the individual who believes in "the Bible alone." Now we know that, in many cases, both sides in a dispute can claim that their personal interpretation is inspired, and both may even believe it, but they hold contrary positions and it is possible both are wrong, and we know both can’t be right.

This then is the problem with the claim that personal interpretation is inspired by the Holy Spirit. Things which are contradictory cannot be true in the same sense at the same time. Yet we have several differences based on the personal interpretation of Scripture. Such differences can be based on:

- Understanding of differing languages

- Understanding of historical context

- Understanding of genre

- Understanding of ways of expression

Others exist. However, the personal interpretation of a “KJV only” person who reads literalistically will be different from a person who is aware of these differences. (It often happens that the “inspired” personal reading is actually the fallible personal understanding of the individual, who thinks that because it makes sense, it must be inspired without concern for context)

Since contrary and contradictory interpretations of Scripture cannot both be true, it seems to follow that we need some sort of authority which is protected from error when teaching about that which pertains to salvation and can determine which interpretations are false and which are right.

So let’s add a seventh syllogism to our list:

Syllogism #7

- Things [Inspired by the Holy Spirit] are not [contradictory] (No [A] is [B])

- Some [Personal Interpretation] is [contradictory] (Some [C] is [B])

- Therefore some [Personal Interpretation] is not [Inspired by the Holy Spirit] (Therefore some [C] is not [A])

(You can also use the same syllogism with "contrary" since it is possible for both options to be wrong, while Christians believe that the Holy Spirit does not err)

So we know some personal interpretation may be right, but do not know which ones are. This, by itself, means we are in the same situation as having an inerrant Bible and not knowing what books belong within the Bible: If we can’t know which books go in it, how can we know if it is inerrant. Likewise, if we can’t know whose personal interpretation is inspired, how can we know whether an interpretation is true or not?

In other words, if you have an inerrant Bible and an interpreter who can err, the Biblical Interpretation can err. This would strip the Bible of being authoritative to us. We can use an analogy of a person starving, and the food being on the other side of a fence which we cannot reach through or climb over to benefit from the food. Likewise, if we can’t have a definitive source on who decides which is true and which is not, we can’t ever know if an interpretation is true or not, and we cannot benefit from the truth.

Conclusion

So from these two sets of syllogisms, we can see certain things emerge:

- We have an example of the Church being protected from error in one instance of defining a truth necessary for salvation.

- Since personal interpretations and appeals to a plain sense are contradictory or be contrary, we cannot appeal to these in a general sense to being inerrant.

- In order to know whether an interpretation of the Bible is true or not, we need an authority which can make an inerrant decision as to whether an interpretation is correct or not.

We need to keep these things in mind when we approach the next few articles: On Scripture, History and what the Church claims about herself.